Let’s go beyond Roses are Red

You think that you know poetry? Think again! 12 types of poem explained

Published on September 1, 2025

Credit: Álvaro Serrano

Credit: Álvaro Serrano

Poetry is as diverse as the individuals who write it—from short, playful rhymes to long, heartfelt verses, with some forms following strict rules and others allowing complete freedom. This wide variety enables poets from all walks of life to express themselves in unique ways. Take a look at the following 12 types of poetry. How many of them do you already know?

Ballad

Credit: Rafi Ashraf

Credit: Rafi Ashraf

A ballad, in its most well-known form, is a song. And there is good reason for this: ballads are narrative poems characterized by their melodic rhyme scheme, which lends the poem a musical quality.

Elegy

Credit: Veit Hammer

Credit: Veit Hammer

Unlike ballads, elegies have no strict rules regarding length or structure. However, they do follow one important convention: elegies are always about death. These somber poems are reflective in tone and are written to mourn the loss of an individual or a group. Among the many poems that exemplify this, Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night by Dylan Thomas stands out.

Epic

Credit: Nicholas Mullins

Credit: Nicholas Mullins

As the name implies, an epic poem speaks about things that are vast, complex, and often larger than life. Epics are long and detailed narratives that recount fantastical adventures of heroic characters, who may be either fictional or historical. Some famous examples of epics are The Iliad, The Odyssey, Beowulf, and The Aeneid.

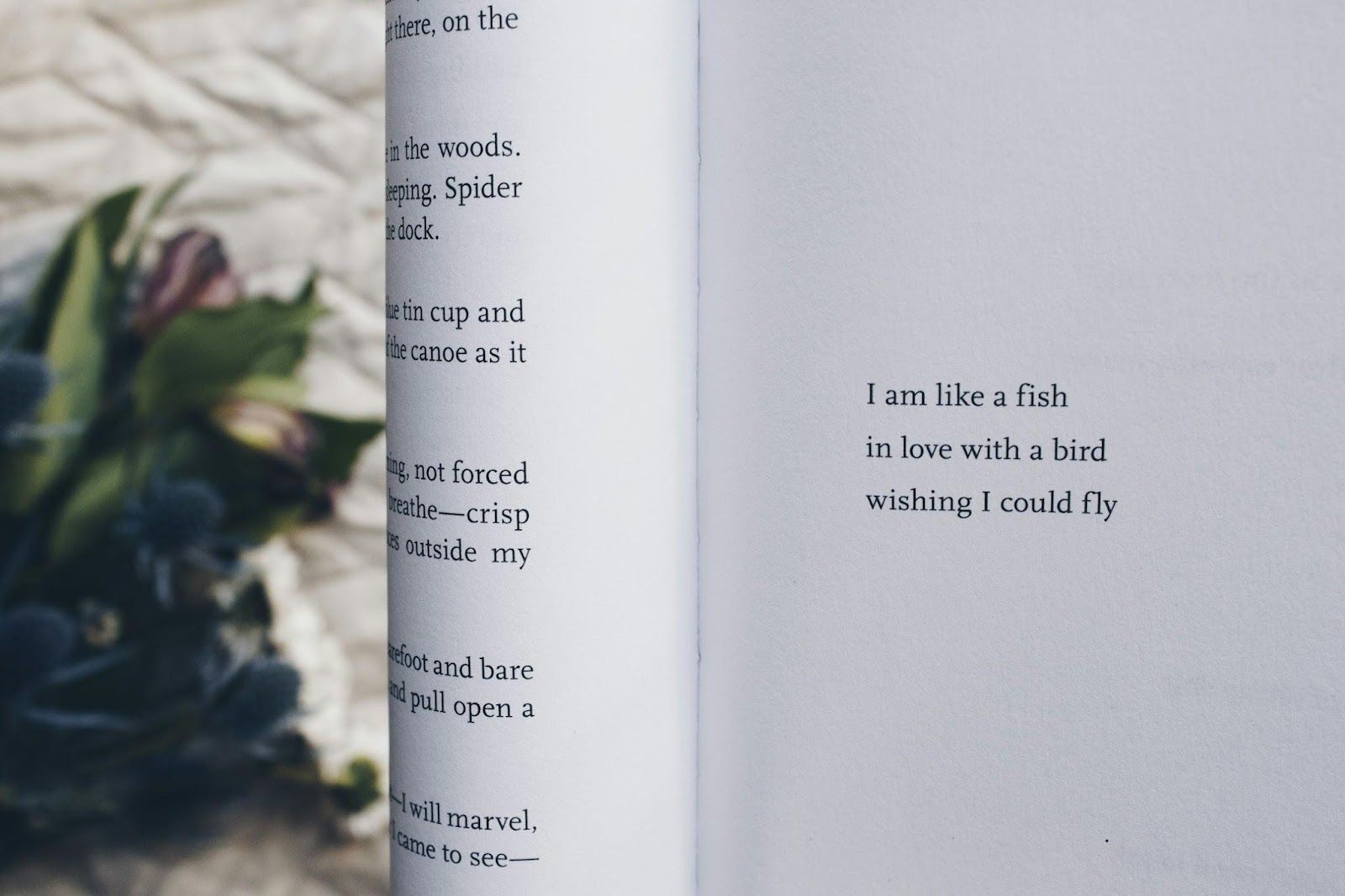

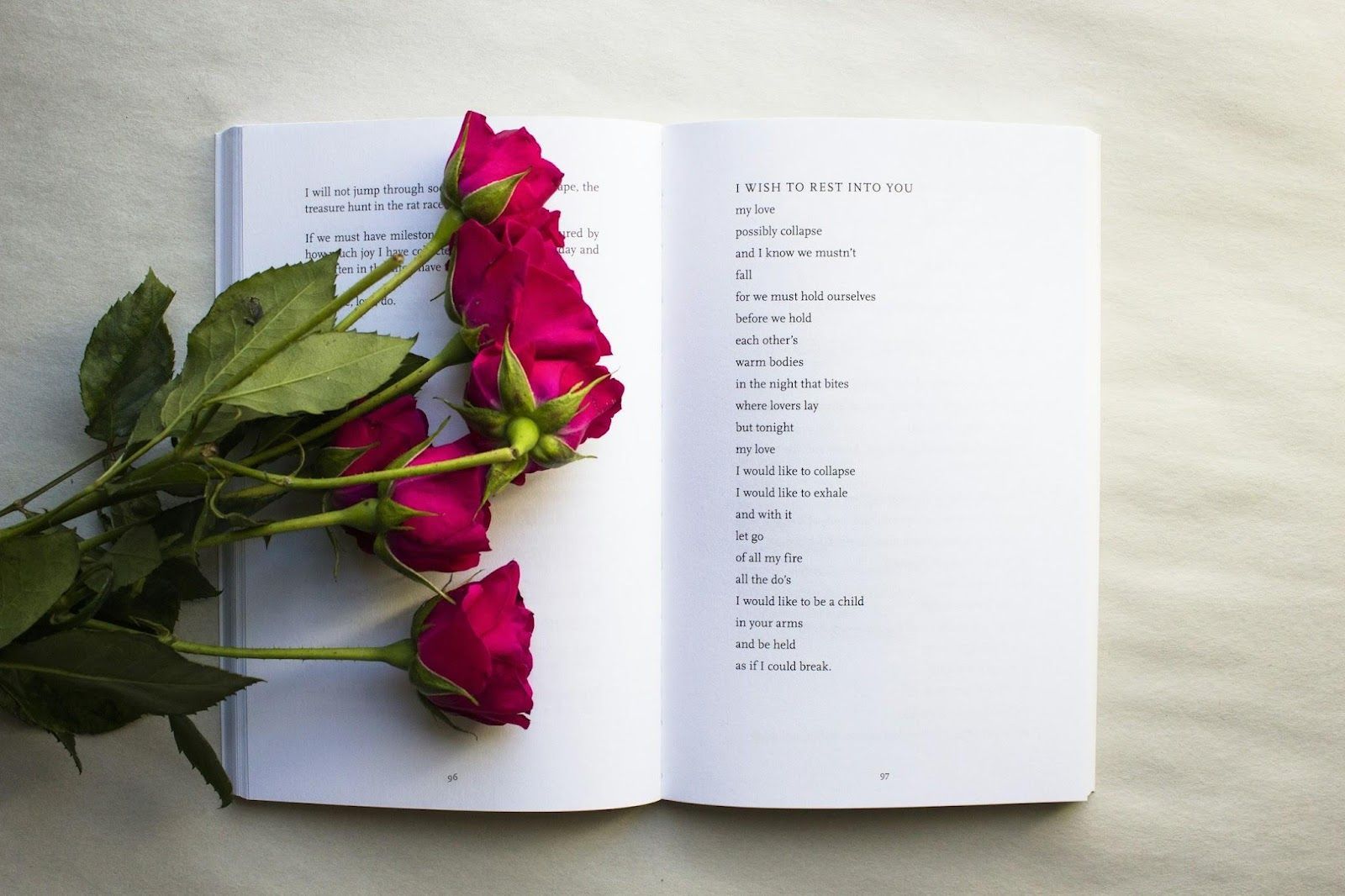

Free verse

Credit: Thought Catalog

Credit: Thought Catalog

Popularized by modern poets like Walt Whitman and T.S. Eliot, free verse poetry is exactly what it sounds like—free. At least when it comes to following any consistent rhyme scheme or meter. It can be long or short, and about any subject. It’s freedom in the most poetic form possible.

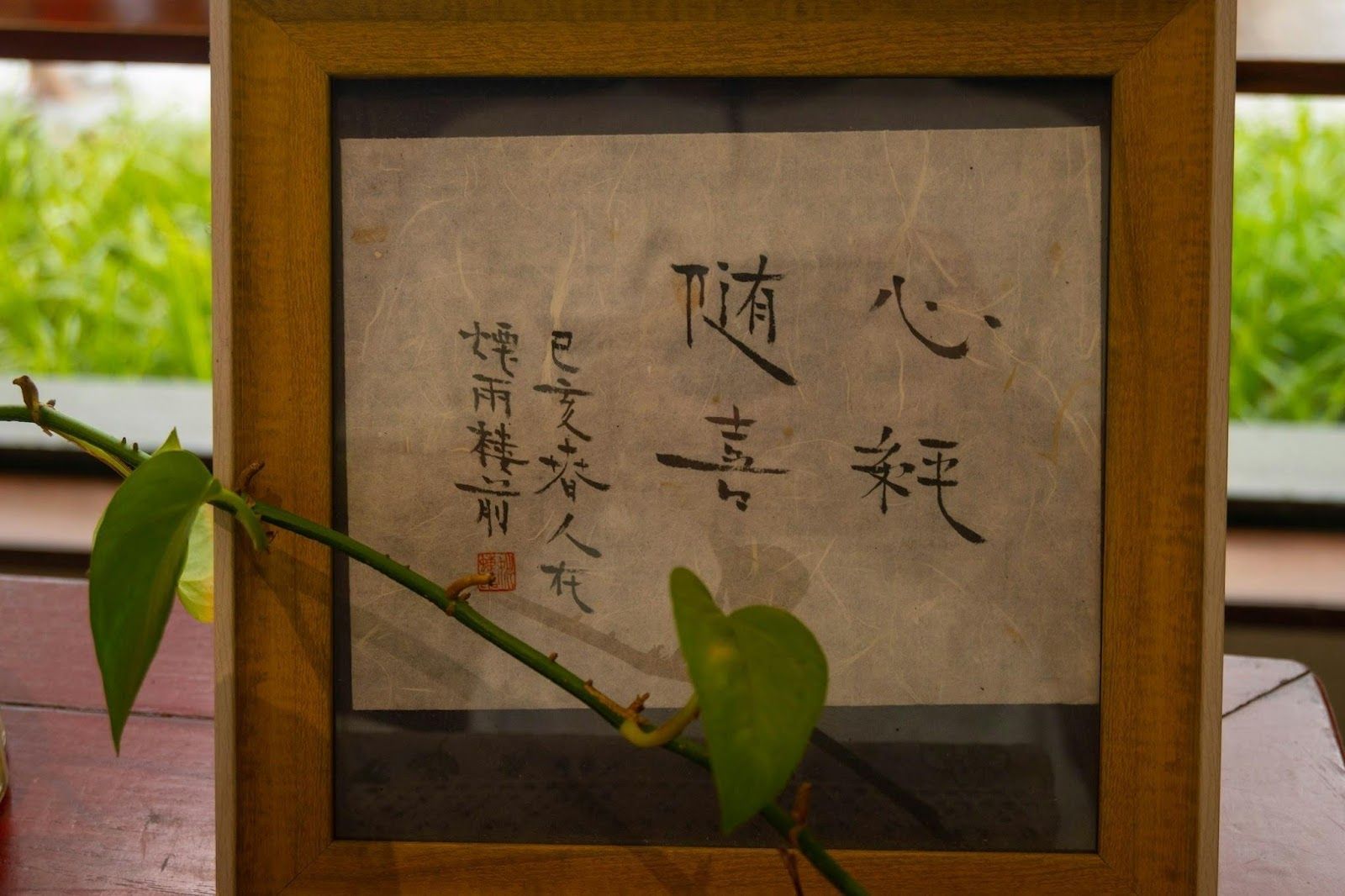

Haiku

Credit: Cun Mo

Credit: Cun Mo

A haiku is a short Japanese poem characterized by its particular form: a five-syllable line followed by a seven-syllable line, and then another five-syllable line. These lines do not rhyme.

Haiku are commonly about nature and often include a "cutting word" that divides the poem into two contrasting or complementary parts.

Limerick

Credit: jules a.

Credit: jules a.

This playful word describes a type of short, humorous poem that originated in the 19th century.

Limericks have five lines and follow an AABBA rhyme scheme. The first, second, and fifth lines typically contain seven to ten syllables, while the third and fourth lines are shorter, usually five to seven syllables. So, not so simple after all!

Ode

Credit: Thought Catalog

Credit: Thought Catalog

Another familiar word, an ode is a poem that praises someone or something. These poems are not required to follow a specific meter, rhyme scheme, or length, though they often adopt a formal and elevated tone. Ode on a Grecian Urn is one of the best-known and widely analysed odes by John Keats.

Ekphrastic

Credit: Jack Finnigan

Credit: Jack Finnigan

A hard-to-pronounce word, ekphrastic poetry refers to poems inspired by visual images or works of art. It does not follow a specific form, structure, or set of rules. What matters most is the emotional connection between the poem and the artwork that inspired it.

Erasure poetry

Credit: Claudio Schwarz

Credit: Claudio Schwarz

We do not know if this form of poetry inspired the pop band of the same name, but in any case, erasure poetry is a form of found poetry in which the poet takes an existing text and crosses out or blacks out large portions of it.

The idea is to create something new from what remains of the initial text, creating a dialogue between the new text and the existing one.

Concrete poetry

Credit: Rainer Bleek

Credit: Rainer Bleek

When Erik Satie, the surrealist French composer, was criticized for writing music "without form," he responded with a piece of sheet music shaped like a pear. Similarly, concrete poetry is designed to create a particular shape or form on the page that reflects the poem’s message.

This form of poetry uses layout and spacing to emphasize certain themes, and poems sometimes take the shape of their subjects.

List poetry

Credit: Glenn Carstens-Peters

Credit: Glenn Carstens-Peters

As simple as it sounds, a list poem consists of a series of things or items. It doesn’t follow any strict rules, though the last line is often funny or meaningful, serving to sum up the entire poem or at least bring some closure to it.

Echo verse

Credit: Thought Catalog

Credit: Thought Catalog

Just like the written counterpart of a real echo, an echo verse repeats the last syllable of each line at the end of that line. This repeated syllable can appear either at the end of the same line or on a separate line directly beneath it.