Did you know history owes these 10 scientists a Nobel Prize?

Published on September 7, 2025

Credit: Stefan Kühn, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Stefan Kühn, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Throughout the more than 120-year history of the Nobel Prize, several scientists have made remarkable discoveries but were never awarded. From Nikola Tesla to Stephen Hawking, these geniuses weren’t properly recognized due to bureaucratic issues, sexism, bad luck, or even their own bad temper. In this article, we’ll look back at 10 scientists who may have been ahead of their time but still deserve to be remembered for their invaluable contributions to humanity.

Stephen Hawking

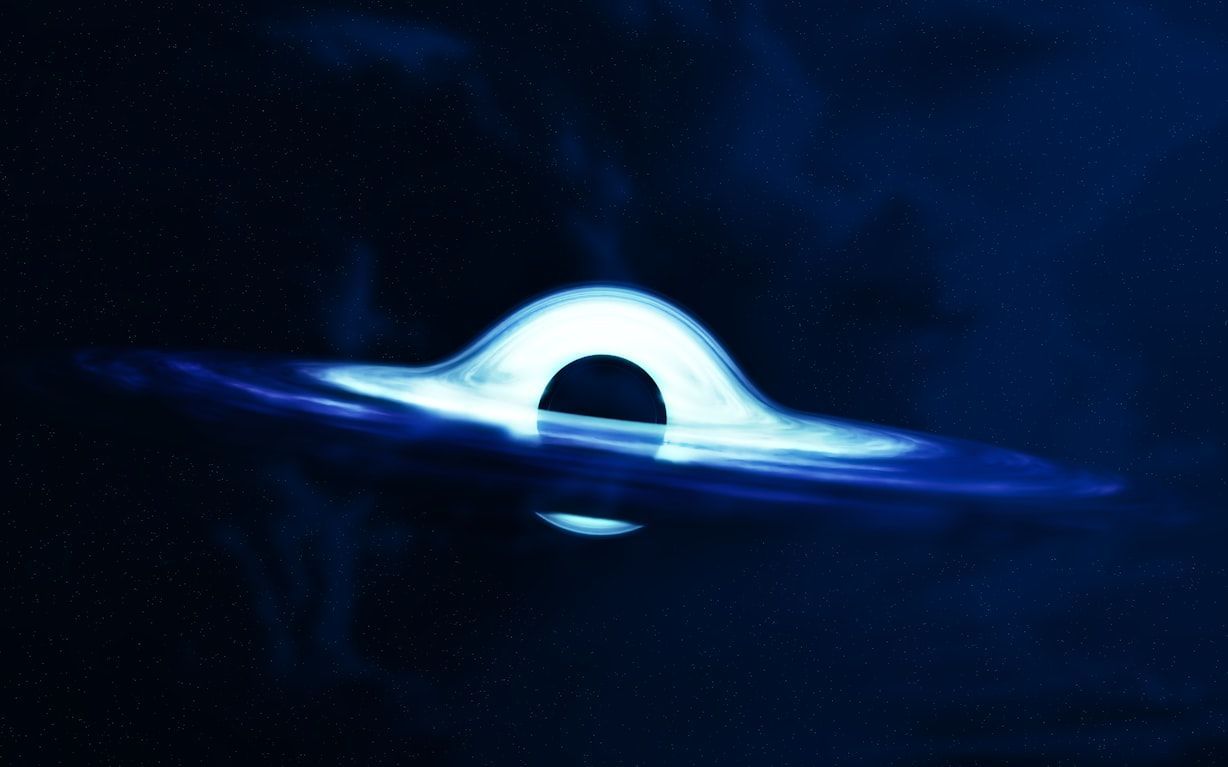

Credit: BoliviaInteligente

Credit: BoliviaInteligente

His studies on black holes earned Stephen Hawking the status of genius. He was one of the most brilliant minds of his generation, yet the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences never awarded him one of the highest prizes given in physics.

The reason? Simply put, to win a Nobel Prize, scientific theories must be confirmed empirically. Unfortunately, current technology doesn’t allow the British astrophysicist's predictions to be fully verified. His work, although crucial to science, couldn’t be fully recognized while he was alive.

Dmitri Mendeleev

Credit: Vedrana Filipović

Credit: Vedrana Filipović

Dmitri Mendeleev was a 19th-century Russian chemist. Even though he developed the periodic table of elements, a huge advancement for science, he never won the Nobel Prize. Back then, the rules stated scientists could only be awarded for recent discoveries, and Mendeleev's work was considered "old."

Years later, the rules changed. Mendeleev was finally nominated in 1906, but he didn’t get it either. Some claim that Svante Arrhenius, one of his rivals and a prominent member of the Royal Swedish Academy, prevented him from receiving the award. The Russian chemist died a year later, so he was never able to receive the prize.

Nikola Tesla

Credit: Published on LIFE, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Credit: Published on LIFE, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

There’s a false assumption that the Serbian-American scientist Nikola Tesla was elected to win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915 along with Thomas Edison, but that he turned it down because of the rivalry between them. Others claim that he rejected it because he disapproved of Guglielmo Marconi’s 1909 award, whom he accused of having stolen the radio patent from him.

The truth is, there is only one reference to Tesla in the Swedish Academy's historical archives, a 1937 nomination that he didn’t end up winning. Yet, to be fair, Marconi's prize should have been shared with Tesla. After all, he was the first to study radio waves in 1891. Due to administrative issues, it was not until the 1940s that a U.S. court determined that Tesla's work did indeed predate Marconi's.

Wallace Carothers

Credit: Anastasia Shuraeva

Credit: Anastasia Shuraeva

In the 1930s, American chemist and inventor Wallace Carothers, who at the time worked for DuPont, discovered condensation polymerization. This process was key to the development of nylon, a polymer used as a textile fiber and in countless industrial applications.

By 1936, Carothers had earned a good reputation and even became the first industrial organic chemist to be accepted into the US National Academy of Sciences. Despite his stature, he was not nominated for the Nobel Prize that year. The chemist, deeply depressed, took his own life a year later, ending any chance of ever winning it.

Lise Meitner

Credit: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Credit: See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The name Lise Meitner may not ring a bell, but we owe this Austrian physicist the first studies on nuclear fission. Like other women in science, her pioneering work is rarely mentioned. At the turn of the century, Lise began working with German chemist Otto Hahn, who would later take the credit for her research.

After World War II broke out, Hahn and Meitner had to separate, but continued to exchange ideas via mail. At the end of 1944, Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry, yet he never mentioned the thirty years of collaboration with Lise that had improved his research.

Douglas Prasher

Credit: Jane Ta

Credit: Jane Ta

In the late 1980s, American molecular biologist Douglas Prasher discovered the gene that expresses the green fluorescent protein used as a marker in biomedical research to observe processes otherwise invisible to the human eye. Prasher’s breakthrough is now widely used in laboratories around the world thanks to his generous decision to openly share his pioneering work.

In 2008, three scientists who followed up on Prasher's research won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. By then, Prasher had lost his job as a scientist and was working as a bus driver in Alabama, United States, to alleviate his family's financial problems. Fortunately, in this case, the award laureates did thank Prasher in their speeches, and, in turn, the biologist was delighted with his colleagues' achievements.

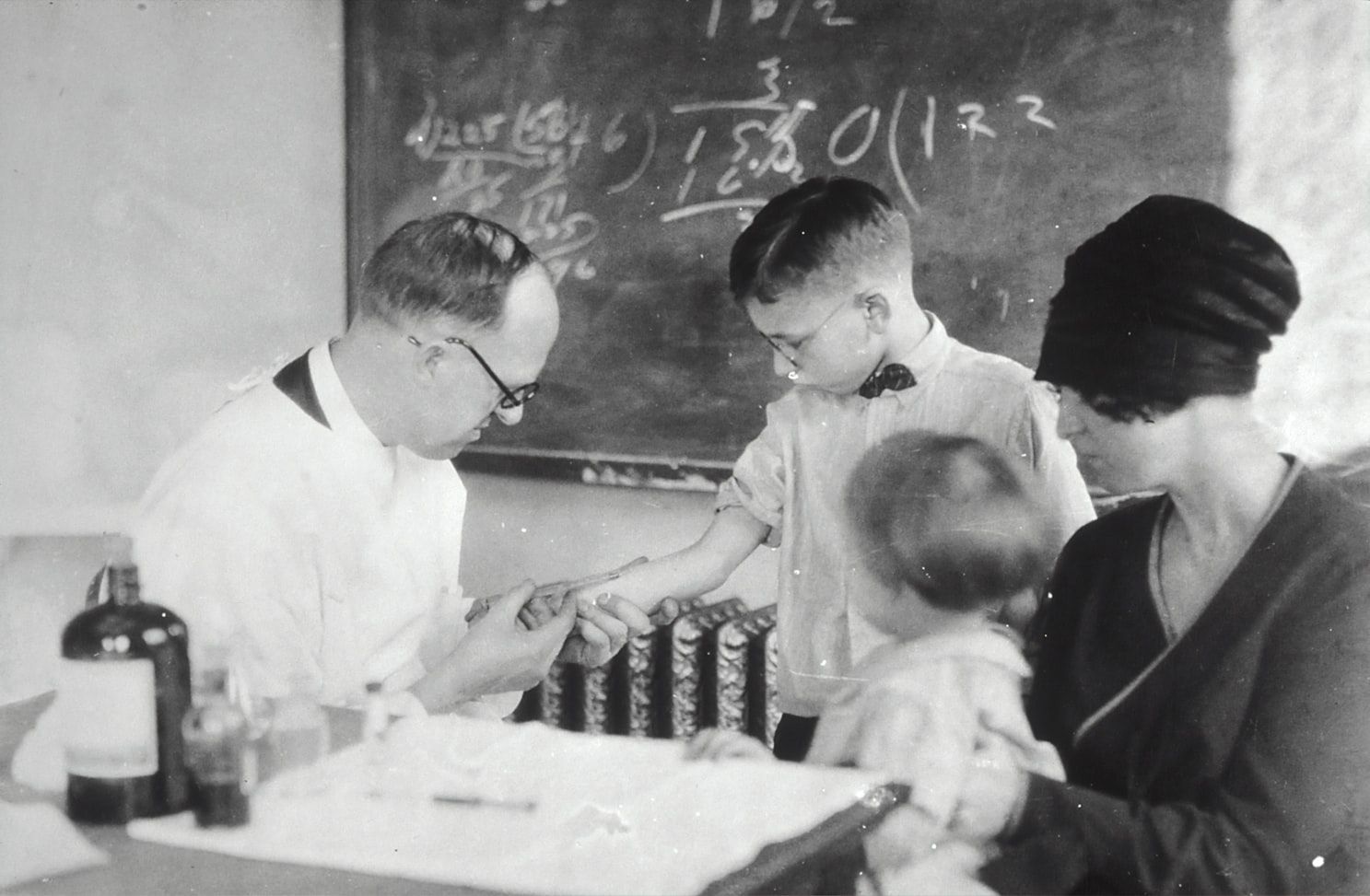

Jonas Salk

Credit: National Cancer Institute

Credit: National Cancer Institute

Despite having developed one of the first successful polio vaccines, American virologist Jonas Salk never received the Nobel Prize. One of the main reasons was that the vaccine was largely based on previous research. Allegedly, Nobel Prizes in Medicine are only awarded to "revolutionary innovations" that introduce new knowledge.

Although the Swedish Academy never recognized Salk's work, it’s important to mention that thanks to his research, on which he refused to receive any profit, millions of vaccinated children in about 90 countries around the world received immunization against the disease. Less than 25 years later, domestic transmission of polio had disappeared in the United States.

Rosalind Franklin

Credit: digitale.de

Credit: digitale.de

British chemist Rosalind Franklin specialized in X-ray crystallography. In the 1950s, while working at King's College London, she developed the technique and instruments that were key to discovering the structure of DNA.

In 1953, the images were released without her permission. When James Watson and Francis Crick were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology for the discovery of the DNA double helix, Franklin had already died of ovarian cancer, probably caused by long hours of exposure to X-rays. Neither of them mentioned her invaluable contribution.

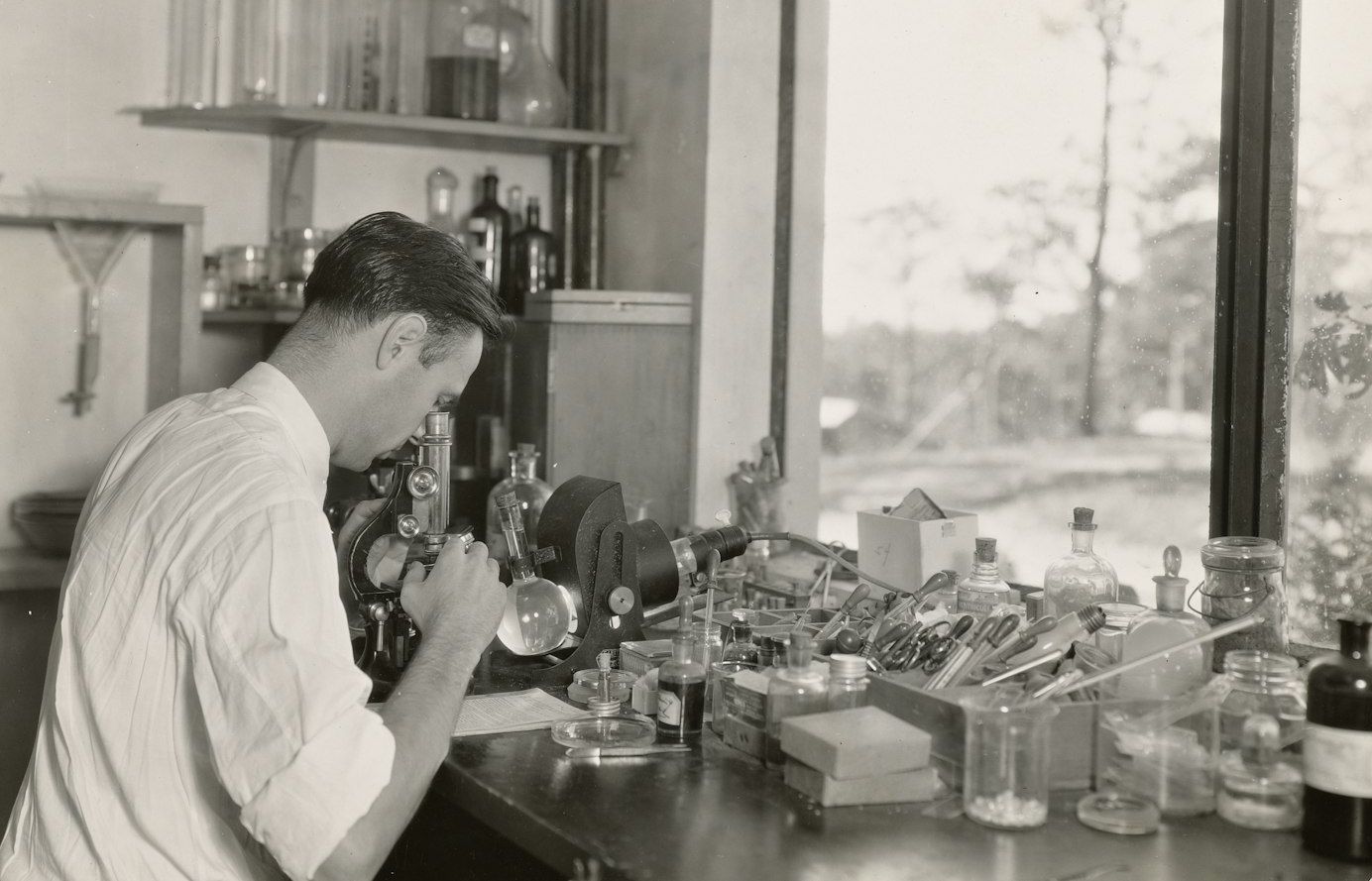

Albert Schatz

Credit: The New York Public Library

Credit: The New York Public Library

At the beginning of the 20th century, Alexander Fleming revolutionized the world of science by discovering the effect of penicillin on bacteria. However, there was still one deadly disease on which penicillin had no effect. Fortunately, in the 1940s, American microbiologist Albert Schatz discovered another antibiotic agent, streptomycin, which could treat tuberculosis.

Yet, it was Selman Waksman, Schatz's supervisor, who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1952 for the discovery of streptomycin. Schatz had signed over his commercial rights and was not even mentioned by the Academy. Years later, he sued Waksman and got half of the royalties and was finally recognized as co-author of the discovery. Schatz was never listed in the Nobel Prize but was awarded the Rutgers University Medal in 1994.

Michael Dewar

Credit: Mehdi Mirzaie

Credit: Mehdi Mirzaie

Michael Dewar, a professor at the University of Texas, was a major contributor to computational chemistry. Despite the significance of his research, he did not win the Nobel Prize. Many believe this was due to his bad temper.

According to reports, he once called a prominent fellow scientist a "disgrace to science" in front of a large audience. He also had heated confrontations with two influential Nobel laureates, William N. Lipscomb and Linus Pauling, who may have blocked his chances of ever winning the award.